What happens when you mix big data and politics? An explosive article in last weekend’s Guardian investigated the links between Brexit, Trump and a data mining firm called Cambridge Analytica. But did it uncover a shady political coup or the logical (and legal) next step in campaigning?

The article from Carole Cadwalladr, is an in-depth study of how both major ‘leave’ campaigns in the EU referendum and the Republican’s 2016 presidential election campaign both made use of data mining, and uncovers potential links between them all in the form of Cambridge Analytica and a more obscure company called AggregateIQ.

Cambridge Analytica is owned by Robert Mercer, a computer scientist and pioneer in early artificial intelligence. It’s vice president during the EU referendum was Steve Bannon, who is now a key advisor to President Trump and former editor of the highly partisan online news blog Breitbart.

One of the most striking quotes from the report comes from an anonymous former employee from Cambridge Analytica, who described what they did as “Psychological operations – the same methods the military use to effect mass sentiment change. It’s what they mean by winning ‘hearts and minds’. We were just doing it to win elections in the kind of developing countries that don’t have many rules.”

The key point behind the article was this: Just as Google knows a new restaurant you might like, why wouldn’t it know an issue you might have strong opinions on?

Using the same programmatic marketing techniques that advertisers use, what’s stopping political campaigns from nudging you towards voting for them because they have similar views on that issue?

Just a harmless personality test? Facebook data was the key

So how was this done? Leave.EU worked with Cambridge Analytica, using Facebook data to determine personality traits, political partisanship, sexuality and much more from people’s likes. It harvested new Facebook data by paying people to take a personality quiz which also allowed not just their own Facebook profiles to be data mined, but also those of their friends – a process allowed by the social network at the time (it has since been changed).

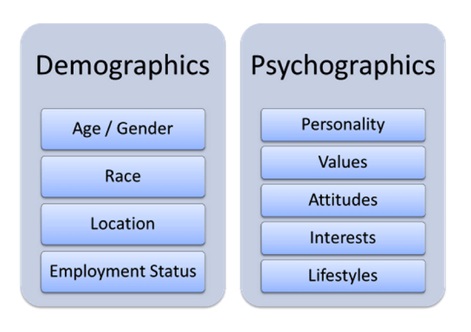

The company also bought consumer datasets (such as magazine subscriptions to airline travel) and cross-matched these with the “psychographic” data to voter files. It matched all this information to people’s addresses, their phone numbers and often their email addresses.

From this, the Leave campaign as able to glean “persuadable” voters. The report claims that this meant the group could “target people high in neuroticism, for example, with images of immigrants “swamping” the country.The key is finding emotional triggers for each individual voter.”

See an example below:

While it would be impossible to influence everyone, the aim of the data mining was to influence people who do not normally vote, persuading those sympathetic to your cause to get out and vote, while discouraging potential supporters of your opponent from voting at all. This is supported by the blog from Dominic Cummings, head of the Vote Leave campaign, who writes that Brexit came down to “about 600,000 people – just over 1% of registered voters”.

But aren’t most Trump and Brexit voters older? Do they even use social media?

While youngsters are certainly more tech savvy, one reason why targeting Facebook works for political persuasion is that increasingly its attracting older users, and the social network is increasingly being used more to share news (at the expense of more personal posts and photos).

See this short documentary from the BBC following a group of voters in Knoxville, Tennessee, who backed Trump and share his disdain for the “mainstream media”.

Following the money

During the run up to the EU referendum vote, there were two major groups campaigning for the UK to leave the European Union. The official “Vote Leave” and the more radical, UKIP affiliated “Leave.eu”. Rules meant that neither group could co-operate, unless campaign expenditure was declared, jointly.

As the Guardian article progresses, author Carole Cadwalladr, looked at potential links, both declared and undeclared, between the campaigns on both sides of the Atlantic. She quotes as LSE report published in April 2017 that concluded UK’s electoral laws were “weak and helpless” when it comes to policing new forms of digital campaigning.

The author identified a small Canadian company called AggregateIQ that the official Vote Leave campaign spent more money on than any other than organisation during the campaign. But the links between AggregateIQ and Cambridge Analytica were even more interesting- being also used by the Trump campaign and Leave.eu.

To demonstrate just how effective these data mining techniques are, view this October 2016 presentation, made a month before the Trump victory, from Alexander Nix, CEO Cambridge Analytica:

Lessons for marketers: The science of persuasion

While much of the Guardian report can sound alarming, signalling a dangerous new phase of unregulated political manipulation, some key questions arise. Isn’t this just smart marketing? And why didn’t their opponents- Stronger In and the Democrat’s 2016 presidential campaign, make better use of similar techniques?

One consistent theme across both the Trump victory and the Brexit success was their use of advanced marketing techniques. These campaigns utilised the power of emotion to drive their narratives and took advantages of the complexities of Big Data to direct those messages at key segmented groups that could have made all the difference in such a tight race.

The recent victories were not merely political successes, but demonstrations of the immense potential of advanced marketing and advertising methods.

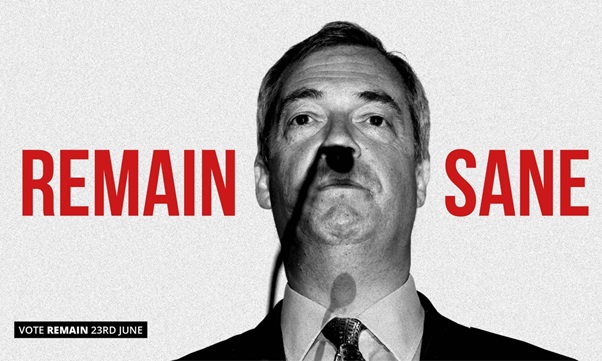

By contrast, the Remain campaign failed to use emotions in their campaign material. For example, see this rejected campaign poster from Saatchi&Saatchi which might have swung a few voters with a powerful (albeit bad taste) message:

One key takeaway from the Trump campaign use of advanced digital marketing strategies can be found in this quote from Steven Bertoni, writing for Forbes:

“FEC filings through mid-October indicate the Trump campaign spent roughly half as much as the Clinton campaign did.”

So while the Hilary campaign also used big data- the Trump campaign conversion rates were considerably better.

So beyond the politics, the key remains this: get the right message to the right audience and your products or services will always find more success.