The virtual reality video content market is expected to reach $8.2bn by 2020, overtaking regular video gaming revenues a year earlier, according to new research.

The study, from Ovum, indicates that virtual Reality is set to be one of the biggest game-changing technologies of the decade, but there is still confusion around how to monetise it.

Virtual reality is changing the landscape for consumers but many are uncertain about how this will impact their daily lives in the next few years, while the potential for digital service providers is also in the early stages of being exploited.

Ovum’s report highlights the importance of virtual reality video vs virtual reality gaming and the key challenges content creators and operators will need to overcome to engage consumers and generate revenues.

Key findings:

· The virtual reality video content market is expected to reach $8.2 billion by 2020 which will present exciting new revenues for those in the TMT industry

· VR video will surpass VR video games by 2019, in contrast to current expectations of VR gaming

· There will be 150 million VR headsets manufactured by the end of 2017 in response to growing consumer demand

VR video will be worth $8.2bn by 2020 globally

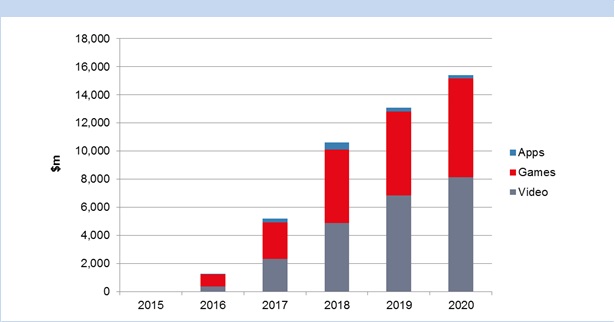

Ovum forecasts that VR video will generate revenues of $8.2bn by 2020, which is impressive given that today consumer revenues around VR video are effectively zero – most content is either brand promotion, personal video, or technology demos. It also means that video will surpass videogames as the number one revenue category within VR in 2019, as millions of consumers get portable mobile headsets and spend modest sums on content.

Figure 1: Forecast of VR video revenues, 2015–20

Five forms of VR video

• Normal SD/HD video in a VR environment.

Essentially, this is the kind of service Netflix and Hulu have already announced for a variety of VR platforms, and is the killer app for “virtual cinema” headsets like the Avegant Glyph. When the user puts the headset on they can place themselves in a virtual environment (cinema, plush apartment, on the moon) with a flat “screen” in front of them on to which a video stream (SD or eventually HD) can be rendered. Aside from some application architecture for VR controls and the environments, this is pretty much like streaming video to a tablet or smartphone – user authentication, frame rate, and catalogue are key.VR does offer some interesting future opportunities here, such as shared viewing with friends regardless of their location, and Minority Report–like navigation between video streams and services (tantalizing for sports fans wanting to watch multiple games or fiddle with replays).

• “3D film” in a VR environment.

An extension of normal streaming video would be to use an existing 3D film source for viewing. This would not be as immersive as a true VR video, but more like an “embossed” version of a flat 2D film – or like one of those pop-up greeting cards so you would not be able to move around the back of the scene even on rails. Given 3D film has largely failed in the home and been relegated to cinema experiences, this is never likely to be a major usage scenario especially given how clumsy the 3D films will look in VR.

• 360-degree video.

Opinions vary as to whether much of this should really be called VR video. While it is the single biggest application for mobile and promotional VR headsets and what most 360-degree cameras capture, most of these videos are not stereoscopic. This means you are effectively filming all around you (even above and below in some cases), but generating a standard 2D video. So watching these videos is like sitting in a fishbowl with video “pasted” on to the interior surfaces. It works great for landscapes and long shots, but falls apart as soon as objects/people are nearer as there is no depth perception.

• Noninteractive/on-rails immersive VR video.

The most common type of VR video will be on-rails experiences where a cameraperson has used a 360-degree stereoscopic camera to capture a scene. You will be able to “move” through the scene as it progresses, and look around and focus on different areas of the video, but you will not be able to interact in any way with its contents. Most of the early VR documentaries and shorts work like this. Alternatively, you may be presented with multiple locations that you can “hop” between to view an event (for example, track-side, bleachers, and sky-cam in a sports arena). Incidentally, the term “on-rails” comes from videogames – “on-rails” shooters like Time Crisis or House of the Dead – popular light-gun games that did not give you any control of where the protagonist went.

• Fully immersive VR video.

To truly utilize the VR platform, video should be fully interactive, where you can walk around in a scene as you please – more like a play or art installation than film. So far this is not really possible from a technical perspective, as the players would have to be rendered on the fly rather than pre-packaged. Computation photography offers hope here, but is still largely a theoretical space with a few pioneers like Lytro and more recently Intel leading the charge. This also raises questions about the structure of entertainment – how can you successfully advance a story if you are not sure the viewer is looking at the right thing. This form of VR video is getting to the point where it will be indistinguishable from VR gaming/interactive experiences.

Source: Ovum