Were the Luddites wrong after all? A new report indicates that technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed in the past 144 years by shifting work to other areas.

The UK study, from financial services company Deloitte, examined census data for England and Wales stretching back to 1871.

The authors, Ian Stewart, Debapratim De and Alex Cole, found that rather than making human workers redundant, technology has simply shifted work into other areas.

The report, entitled Technology and people: The great job-creating machine, has looked at long-term historical trends relating to new technologies and their impact on employment and society, and found that in almost all instances the effect is positive in the long term.

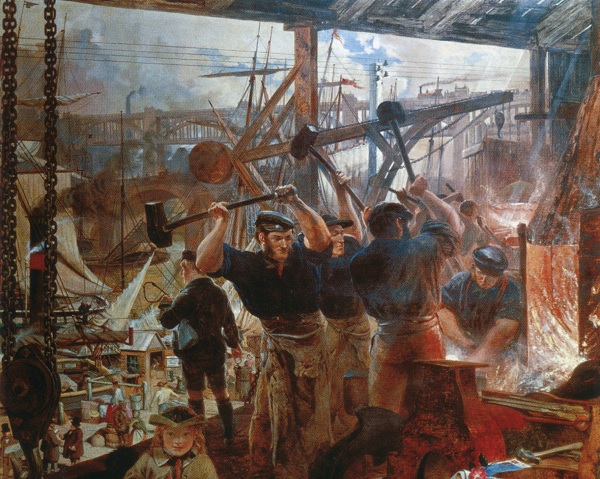

The report authors noted that many dangerous or boring jobs have been mechanised since the Industrial Revolution.

“Routine jobs, both cognitive and manual, have suffered most, because technology can readily substitute for labour. Job losses in white collar occupations involving the processing of paperwork and in manufacturing speak to this,” they said.

For instance, the number of people involved in washing and laundering was 200,000 in 1901 in a population of 32.5 million. In 2011, of a population of 56.1 million, 35,000 people worked in the sector, and mostly in commercial launderettes.

“A collision of technologies, indoor plumbing, electricity and the affordable automatic washing machine have all but put paid to large laundries and the drudgery of hand washing,” the report explained.

Rising wages and more leisure time has meant that people are spending more money on grooming now than they were during the Victorian period – as a result, there is now one hairdresser for every 287 people in England and Wales, as opposed to one for every 1,793 in 1871.

While wages have risen and leisure time has increased, the prices of goods have also fallen – automation and technological advances means that the cost of things like cars, TVs and kitchen appliances have fallen dramatically, even over the last couple of decades, the study found.

The report does acknowledge that jobs in certain fields have declined over the rise of technology, but says that “the stock of work is not fixed” – meaning that when some professions decline, others often spring up in their place.

The report argues that this should all serve as a positive sign from history that, while jobs can be lost in certain areas because of technology, it ultimately leads to improvements for society in terms of productivity and new and better jobs.

“Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labour than at any time in the last 150 years,” it said.

“Technology has transformed productivity and living standards, in the process creating new employment in new sectors. Machines will continue to reduce prices, democratising what was once the preserve of the affluent and furnishing the income for increased spending in new and existing areas.

“The work of the future is likely to be varied and have a bigger share of social interaction and empathy, thought, creativity and skill.”

However, the authors admit that it is impossible to predict exactly where future jobs will come from and what societies of the future will require.

“Who, for instance, could have predicted 60 years ago the role that coffee shops, gyms and mobile telephony would play in our lives in the early 21st century?” they said.